Roberto Capucci stands as one of the most innovative figures in the world of haute couture. Born in the heart of Rome, he transformed the art of dressmaking into something akin to sculpture. His designs, often described as “sculpture dresses,” blend the precision of architecture with the fluidity of fabric. Capucci’s work challenges the boundaries between fashion and fine art, creating garments that are not merely worn but inhabited like living forms. Over seven decades, he has crafted silhouettes that evoke ancient columns, natural curves, and ethereal volumes, earning him acclaim as a pioneer of futuristic style.

What sets Capucci apart is his unwavering commitment to form and structure. He views clothing as a three-dimensional expression, where pleats, folds, and rigid elements mimic the human body’s sacred geometry. His creations have graced museums and catwalks alike, influencing generations of designers who seek to elevate fashion beyond the ephemeral. Yet, Capucci’s journey was not one of overnight success. It began in the modest ateliers of post-war Italy and evolved through bold experiments that sometimes puzzled contemporaries. Today, at 94, his legacy endures through a vast archive and a foundation dedicated to preserving his vision.

This article explores Capucci’s life and work in detail. It traces his roots, the sparks of inspiration that ignited his career, and the groundbreaking collections that defined his oeuvre. By examining his philosophy, we uncover how he sculpted “sacred silhouettes” – garments that honour the body’s divinity while pushing the limits of material possibility. Through exhibitions and awards, Capucci’s influence ripples across continents, reminding us that true fashion is timeless art.

Early Life in Rome

Roberto Capucci entered the world on 2 December 1930, in the bustling city of Rome, Italy. The Eternal City, with its layered history of ruins, fountains, and baroque facades, would later echo in his designs. Growing up in a modest family, Capucci found early fascination in the everyday elegance of the women around him. His mother, sister, and aunts dressed with a quiet sophistication that captivated the young boy. Their garments, simple yet harmonious in colour and proportion, sparked his innate sense of beauty. Rome itself was a classroom without walls. The Colosseum’s arches and the Pantheon’s dome taught him about volume and light, concepts he would later translate into fabric.

The post-war era shaped Capucci’s formative years. Italy was rebuilding from the devastation of the Second World War, a time when rationing limited luxuries but creativity flourished. Fashion became a form of quiet rebellion, a way to reclaim joy through personal expression. Capucci recalled how observing his family’s attire ignited his passion: “I have always designed clothes because I enjoyed it.” These domestic scenes were his first sketches, mental drawings of how cloth could drape and define the female form. Unlike many designers drawn to glamour, Capucci’s entry into fashion was organic, rooted in familial intimacy rather than grand ambition.

Family played a pivotal role beyond inspiration. His younger brother, Fabrizio Capucci, and niece, Sabrina Capucci, both pursued acting careers, suggesting a household alive with artistic energy. Though details of his parents remain sparse, it is clear that Capucci’s environment nurtured a sensitivity to aesthetics. Rome’s vibrant street life – vendors hawking silks, tailors mending hems – further immersed him in the tactile world of textiles. By his teenage years, he was sketching dresses on scraps of paper, envisioning garments that went beyond utility to evoke emotion.

This period was not without challenges. Economic hardship meant resources were scarce, yet it honed Capucci’s resourcefulness. He learned to appreciate the inherent qualities of materials, from wool’s warmth to silk’s sheen. These early experiences laid the groundwork for his philosophy: fashion as a dialogue between body and environment. As he later reflected, nature and human artistry were intertwined muses, with Rome as their eternal stage. Capucci’s childhood thus emerges not as a mere prelude but as the fertile soil from which his sculptural vision would grow.

Education and Artistic Foundations

Capucci’s formal education polished the raw talent he discovered at home. He enrolled at the Liceo Artistico in Rome, a school renowned for fostering visual arts. There, he delved into drawing, painting, and the principles of composition. The curriculum emphasised harmony and balance, skills essential for any aspiring designer. Capucci excelled, his notebooks filling with studies of light on marble and shadow on silk.

From the Liceo, he progressed to the Accademia di Belle Arti, Italy’s prestigious academy for fine arts. This institution, with its rigorous ateliers, exposed him to masters who shaped his worldview. Among his teachers were Marino Mazzacurati, a sculptor known for monumental forms; Marcello Avenali, a painter of luminous landscapes; and Libero De Libero, a poet-artist who blended words with visuals. These mentors encouraged Capucci to see beyond the flat canvas, urging him to think in three dimensions. Mazzacurati’s influence was particularly profound, teaching him how stone could be carved to suggest movement – a lesson Capucci applied to pleating fabric into waves.

At the Accademia, Capucci honed his skills in colour theory and proportion. He spent hours dissecting Renaissance masterpieces, analysing how Michelangelo’s figures balanced power and grace. These studies revealed fashion’s kinship with sculpture: both disciplines manipulate space to honour the human form. Capucci’s drawings from this era, now preserved in his foundation’s archive, show early experiments with volume. A simple sleeve might swell like a bell, foreshadowing his later box-like silhouettes.

Yet education was more than academics; it was immersion in Rome’s cultural pulse. Capucci frequented galleries and attended lectures on architecture, drawing parallels between Brunelleschi’s domes and the curve of a corset. He absorbed the city’s syncretic spirit – pagan ruins overlaid with Christian iconography – which informed his view of clothing as “sacred silhouettes.” Garments, he believed, should elevate the wearer, much like a vestment in a cathedral.

By the time he graduated, Capucci was equipped not just with technique but with a philosophy. As he later shared in an interview, “My secondary studies at the Liceo Artistico and then at the Accademia di Belle Arti refined, developed and deepened my innate passion for drawing, colour and proportion.” This foundation propelled him from student to creator, ready to launch a career that would redefine Italian couture.

Launching a Couture Empire

At just 20 years old, in 1950, Capucci opened his first atelier on Via Sistina in Rome. This narrow street, lined with artisan shops, was an ideal cradle for his ambitions. The space was humble – a single room with sewing machines and bolts of fabric – but it buzzed with possibility. Capucci designed every piece himself, sketching late into the night. His early clients were local women seeking bespoke elegance, and word spread quickly through Rome’s social circles.

The turning point came in 1952 with his debut at the Sala Bianca in Palazzo Pitti, Florence. This white-walled chamber, dubbed the “White Hall,” was the epicentre of Italy’s emerging fashion scene. Organised by Giovanni Battista Giorgini, the event showcased young talents to international buyers. Capucci presented alongside veterans like Vincenzo Ferdinandi and Germana Marucelli. His collection featured structured coats and flared skirts, blending post-war practicality with artistic flair. Critics noted the precision: seams sharp as chisel marks, hems falling with architectural grace.

That same year, Capucci staged his first catwalk show in Rome, covered by journalist Oriana Fallaci for Epoca magazine. Fallaci praised his ability to make fabric “sing,” capturing the youthful energy of his designs. These successes marked Italy’s haute couture renaissance, as the nation asserted its style against French dominance. Capucci’s work, rooted in Roman grandeur, symbolised this resurgence.

By 1958, innovation defined him. He unveiled the Linea a Scatola, or Box Line – rigid, geometric dresses that squared the female silhouette like modernist furniture. This collection earned a fashion award from Boston, shared with Pierre Cardin and James Galanos. Buyers from Filene’s department store in the US lauded its boldness, proving Capucci’s appeal transcended borders. The Box Line was no gimmick; it was a manifesto, challenging soft femininity with hard edges.

Expansion followed swiftly. In 1960, he received an American fashion award, for his haute couture and ready-to-wear lines. Paris beckoned in 1961, where reviews hailed him as “the best creative designer of Italian fashion.” By 1962, he had opened an atelier at 4 Rue Cambon, steps from Coco Chanel’s salon. Christian Dior himself congratulated him, calling Capucci the finest of Italian talents. Neighbours whispered of rivalry, but Capucci focused on creation, incorporating plastics and stones into garments that shimmered like jewels.

These years solidified his reputation. From Rome’s ateliers to Paris’s salons, Capucci built an empire on vision alone. His shows were theatrical: models gliding like statues come to life, fabrics rustling like whispers from antiquity.

Sculpting Silhouettes: Signature Designs and Collections

Capucci’s genius lies in his sculptural approach. He treats fabric as clay, moulding it into forms that transcend wearability. His “sculpture dresses” – rigid yet ethereal – are his hallmark. Inspired by nature’s geometries, from nautilus shells to mountain folds, these pieces invite the body to inhabit art.

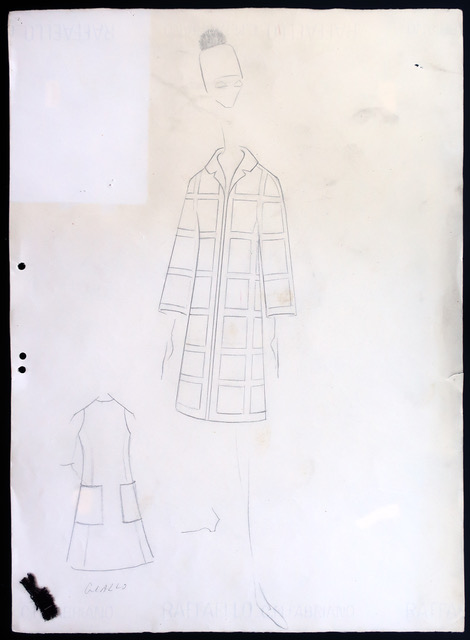

The 1960s brought experimentation. He introduced double-breasted overcoats with exaggerated shoulders and butterfly trousers that flared like wings. The Optical line played with patterns, creating illusions of movement on the Paris catwalks. These designs anticipated the space-age trend, blending couture with futurism. Capucci’s method was meticulous: starting with sketches, he collaborated with artisans – plissé experts, embroiderers, cutters – to realise his visions. “Designers do not help me,” he insisted. “I design every piece of clothing by myself because it’s my passion – I enjoy it; I love it.”

The 1970s marked his sculptural peak. In 1971, a collection drew from Pre-Raphaelite painters, with flowing gowns evoking Rossetti’s muses. This was exhibited at the Museum of Etruscan Art in Villa Giulia, Rome – the first time his designs entered a museum. Fabrics cascaded like Renaissance drapery, colours rich as oil paints. Then came the Column Dress in 1978, his seminal “Colonna” silhouette based on the Doric column. Crafted from silk and stiffened with horsehair, it rose vertically, transforming the wearer into a classical pedestal. This piece, shown in Milan, stunned audiences with its austerity and poise.

One of his most iconic creations is the Nove Gonne gown from this era. A slim shift of lipstick-red taffeta enveloped by nine tiered circular skirts, it mimicked the concentric ripples of a pond disturbed by a stone. Capucci studied natural forms obsessively, translating their mathematics into thread. The gown’s layers built volume without bulk, a feat of engineering disguised as poetry.

The 1980s and 1990s saw global outreach. In 1983, Tokyo hosted his first Asian show, where kimono-inspired pleats met Western structure. New York followed in 1985, with collections blending straw, stones, and precious metals. By 1990, the exhibition “Roberto Capucci, l’Arte nella Moda – Volume, Colore, Metodo” at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence celebrated his method: volume as architecture, colour as emotion, technique as ritual.

Later works reaffirmed his evolution. In 1995, for the Chinese government, he showcased 64 iconic sculpture dresses at Peking University, lecturing on East-West fusion. India profoundly influenced him, its vibrant saris and temple carvings inspiring fluid yet monumental forms. The 2007 Cerchio in Raso, a circle of satin evoking halos, honoured Florence’s Renaissance. In 2010, at Xi’an’s Daming Palace, he presented 10 new pieces drawing from Tang dynasty robes, merging antiquity with modernity.

Capucci’s archive boasts 439 historical dresses, 500 signed illustrations, and 22,000 drawings – a testament to his prolific output. Each collection was a chapter in his ongoing dialogue with form, where fabric became flesh, and silhouette, sacrament.

International Acclaim and Cultural Impact

Capucci’s reach extended far beyond catwalks. In 1968, he returned to Italy, designing costumes for Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Teorema, draping Silvana Mangano and Terence Stamp in ethereal whites that amplified the film’s metaphysical themes. This foray into cinema highlighted fashion’s narrative power.

The 1970 show at Villa Giulia’s Nymphaeum was revolutionary: models in low-heeled boots and minimal makeup paraded amid Etruscan artefacts, blurring art and life. Capucci left the Camera Nazionale dell’Alta Moda in 1980, opting for independent presentations that allowed unfiltered creativity.

Exhibitions cemented his status. The 1991 show at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum juxtaposed his gowns with Habsburg treasures. Stockholm’s Nordiska Museet hosted him in 2001, while Turin’s Venaria Reale featured retrospectives in 2007 and 2016. The 2011 Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition, “Roberto Capucci: Art into Fashion,” was his US debut. Over 80 works, including the Colonna dress and Florence homages, portrayed him as a “study in form,” fusing art, architecture, and nature. Curator Dilys Blum noted how Capucci’s creations offer “a magical and unforgettable experience,” engaging all senses.

Venice Biennale in 1995 invited him as a guest, affirming his artistic credentials. In 2012, Palazzo Fortuny hosted a survey, and he launched a young designers’ competition, awarding winners at Milan’s Royal Palace in 2013. Even in 2025, an exhibition at Villa Pisani in Strà continues his dialogue with Venice’s lagoon light.

Awards underscored his impact: the 1958 Boston prize and 1960 American award marked early triumphs, while international press dubbed him “the Givenchy of Rome” or “lite Balenciaga.” Contemporary designers, from Alexander McQueen to Rei Kawakubo, cite him as muse, drawn to his structural daring.

The Foundation and Enduring Vision

In 2005, Capucci founded the Roberto Capucci Foundation to safeguard his legacy. Housed at Villa Bardini in Florence since 2007, it serves as museum and archive, hosting workshops on plissé and colour. The foundation organises seminars for youth, emphasising craftsmanship amid fashion’s democratisation.

Capucci mentors emerging talents, advising focus on quality prêt-à-porter as haute couture wanes. “Haute couture is a profession that is disappearing,” he observes, yet his passion endures. Collaborations, like the 2010 audiovisual Il Gesto Sospeso at Rome Fashion Week, blend his designs with technology.

His philosophy remains rooted in wonder: “Nature is my first source of inspiration, then comes the work of man the artist: the great painter, architect and musician.” For Capucci, creation is holistic – art, beauty, emotion, music, poetry intertwined.

A Legacy Etched in Fabric

Roberto Capucci’s contributions redefine fashion as sacred architecture. His silhouettes, sacred in their reverence for form, inspire awe. Through foundations and exhibitions, his work ensures that the sculptor’s hand endures, guiding future generations toward beauty’s eternal lines.